Black History Month 2026: Spotlighting youth

Black History Month in Canada

In 1995, the Government of Canada declared February as Black History Month. This federal recognition followed activism at the municipal and provincial levels to designate February as a time to celebrate the many contributions and achievements of Black Canadians, whose individual and community efforts throughout history have enriched the cultural diversity and prosperity of this nation.

Black History Month in the GTA

Toronto was the first municipality in Canada to proclaim Black History Month in 1979, after the efforts of many individuals and advocacy from organizations such as the Ontario Black History Society.

There are multiple events held across the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) commemorating this significant month, through support of Black-owned businesses, celebrating the achievements of Black Canadians and highlighting Black art and culture. Toronto Public Libraries also host free presentations and workshops on music, books, art, and movies by Black individuals.

On Saturday Feb 21st, the YMCA invites you to join us as we celebrate culture, creativity and community at a free, family-friendly event that will spotlight Black youth. We will be screening, A National Film Board of Canada Production, titled King's Court followed by a panel discussion. There will also be entertainment, light refreshments and raffle prizes!

Spotlighting Black History around the world

Throughout history, Black youth have faced discrimination head-on, organizing actions, resisting oppression, and breaking down barriers to equity. This Black History Month, The YMCA of Greater Toronto is focusing on the transformational contributions of Black youth across the world.

1960 — Ruby Bridges

An image of Ruby Bridges being escorted into William Frantz Elementary School by U.S. Marshals in November of 1960. US Marshals with Young Ruby Bridges on School Steps. Uncredited DOJ photographer, restored by Adam Cuerden (a relatively minor restoration), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ruby Bridges was born in 1954, the year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation in schools was unconstitutional. This ruling required all schools to provide Black students with the opportunity to attend all-white schools.

Ruby successfully completed the entrance exam created to determine which African American children could “succeed within all-white institutions.” Her accomplishment brought her to the attention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had been working tirelessly to eliminate public school segregation.

In 1960, Ruby Bridges became a household name at age 6 as the first African American child in the South to attend the all-white William Frantz Elementary School.

On her first day of school, little Ruby had to be accompanied by U.S. Marshals due to protests from white school board officials, politicians, and parents. In her first year of school, Ruby was the only student in her class. She didn’t use communal spaces in the school — she brought her own lunch for fears of being poisoned in the cafeteria, played indoors with her teacher, avoided the playground, and required a U.S. Marshal escort to use

the washroom. Ruby received support from a child psychiatrist who volunteered to visit the family weekly.

Ruby’s circumstances changed in her second year, when she was integrated into classes with other students. By then, other African American students attended her school, and parents no longer protested outside.

Though Ruby’s family was targeted and her experiences were tainted by blatant racism and violent threats, she never missed a day of school. Today, she remains an active civil-rights icon.

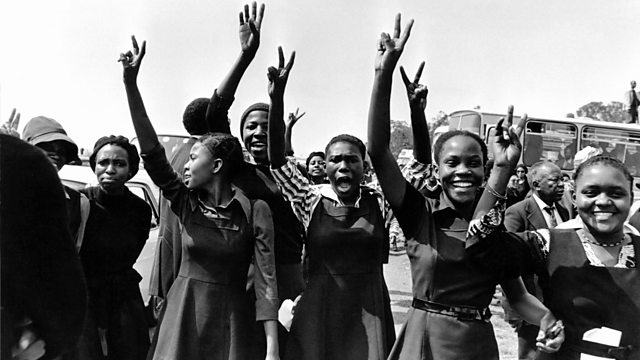

1976 — Soweto Uprising, South Africa

Photo by BBC/Clarity Films/Peter Magubane

Photo by BBC/Clarity Films/Peter Magubane

The Soweto Uprising began on June 16, 1976, when thousands of Black schoolchildren protested having to study Afrikaans, a colonial language that evolved from 17th-century Dutch spoken by Europeans in the Dutch Cape Colony.

Their peaceful, unarmed march against apartheid policies was met with armed police who fired live ammunition [AB1] [CS2] at them. These student-led protests occurred at a time when movements promoting liberation were banned, highlighting the youths’ anger and frustration.

Images of the police brutality spread, sparking many other protests across the country against the racist apartheid government. These protests continued into 1977 and resulted in hundreds (some reports suggest thousands) of deaths nationwide.

Local protests became a full-blown crisis for the apartheid government. Unable to stop the calls for freedom, the uprising paved the way for dismantling apartheid and establishing a democratic South Africa.

2019 — Sudanese Revolution

Photo: Kandake of the Sudanese Revolution. Lana H. Haroun (April 2019)

Photo: Kandake of the Sudanese Revolution. Lana H. Haroun (April 2019)

In late 2018, several cities in Sudan organized demonstrations to protest the rising cost of living. What started as calls for economic reforms quickly evolved into urgent demands for changes to the ruling government.

The government responded with violence and force against peaceful demonstrations, sparking international concern and condemnation. As protests continued into 2019, civilians were teargassed, imprisoned, and many lost their lives.

Women were at the forefront of the protests. As the government tried to stop social media discussions, women harnessed their power to organize. Among them, an icon emerged.

As thousands of people gathered in the streets of Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, local photographer Lana Haroun captured 22-year-old Alaa Salah standing on top of a car. Alass’ finger pointed to the sky as she chanted lines written by Sudanese poet Azhari Mohamed Ali: “The bullet doesn’t kill. What kills is the silence of the people.”

The image of Alaa went viral. People called her Lady Liberty of the Sudanese Revolution and Kandaka of the Revolution, a title for ancient Nubian queens of Sudan, who left a legacy of empowering women to fight for their country and rights.

This single image prompted recognition of the women activists in Khartoum who had shared Sudan’s history for years. People commented that her clothing paid homage to working women, mothers, and grandmothers in the 60s, 70s, and 80s who demonstrated against previous dictatorships.

At 22, Alaa was an architecture and engineering student who became a symbol of young women’s power to inspire and create change.

How the Y celebrates and supports Black youth

The YMCA of Greater Toronto is a charity that ignites the potential in people, helping them grow, lead, and give back to their communities, with anti-racism and cultural diversity being one of our central strategic pillars. We support all youth, including newcomers and Black youth.

To support Black youth in reaching their fullest change-making potential, please consider donating to our Black Achievers Youth Mentorship Program or signing up to be a mentor.